Rural districts are fair again, but can Democrats win them over?

To take advantage of new maps, the party needs to reverse a long pattern of withdrawal and neglect.

On December 10, 2022, I attended the Muskego Christmas parade to do a radio piece for Wisconsin Life on the Milwaukee Dancing Grannies. Alongside the grannies, the high school bands, and local businesses was a small group of Republicans. I wasn’t there to cover the parade per se, so the details in my memory are fuzzy. I don’t remember them getting a big reception or it being anything more than a few people with a banner declaring they were Republicans. But the bigger point is that they were there. Where were the Democrats?

I’ve skewered Wisconsin Democrats before for letting too many Republican candidates go unchallenged, especially Mike Gallagher who has now announced that he will not run for reelection. I even got a tweet in response from someone who said they worked for WisDems who said the party prioritizes races where they’re more likely to win, making it sound like perfectly sensible, fiscal responsibility. I argued that strategy is short-sighted. Part of the pitch Republicans make to rural voters in particular is that Democrats look down on them and don’t care about them. If there is no Democratic presence, that just reinforces that narrative. (And yes, I am using my platform to settle Twitter beef.)

But that’s not the problem in Muskego. Muskego is the home of Rep. Chuck Wichgers, who received national attention for a bill that would ban schools from teaching concepts like “Woke,” “whiteness,” “White supremacy,” “structural bias,” “structural racism,” “systemic bias”... you get the idea. He was also one of 11 Republicans to vote against a bill that expanded access to birth control with one of the most unhinged two-minute long speeches I’ve ever heard, saying birth control “opens up the door to marital infidelity, and it did,” (which received much-deserved laughter), then pivoted to other countries forcing married couples to use birth control (not what was being proposed, at all) allowing government to become the “supreme leader.” Then to top it off, he went on a disjointed spiel about how it's “unnatural” and that men lose respect for women who "have to control the natural reproductive course of the body."

It gets wilder from there, sorry:

"Nature has an intention and when you have that act—when pregnancy naturally occurs, that's nature doing what nature does. The woman then has to counter nature by taking something that is highly systemic and highly invasive, according to the documents and the books that people that are pro the pill stated in their books. That's a science. [Ron Howard voice: It’s really not.] We would begin to see ourselves as the ultimate masters of nature, so when nature does something it's supposed to do and then we say, 'Let's not do that'—we're talking not about getting a pimple if you eat Doritos and eat chocolate [... what?]; that would be contrary to a health movement or nature."

Anyway, whatever that is, it’s clearly ripe pickings for a Democratic challenger. And Wichgers has been challenged, in every election aside from his first. Some of those candidates have done better than others, and the gerrymandered boundaries of the Assembly district he represents probably play a big role. But then here’s the bigger problem: the Democrats are there for the election, but they’re not in the parade, a metaphor for the party’s ongoing support of organizers in these communities and of these communities.

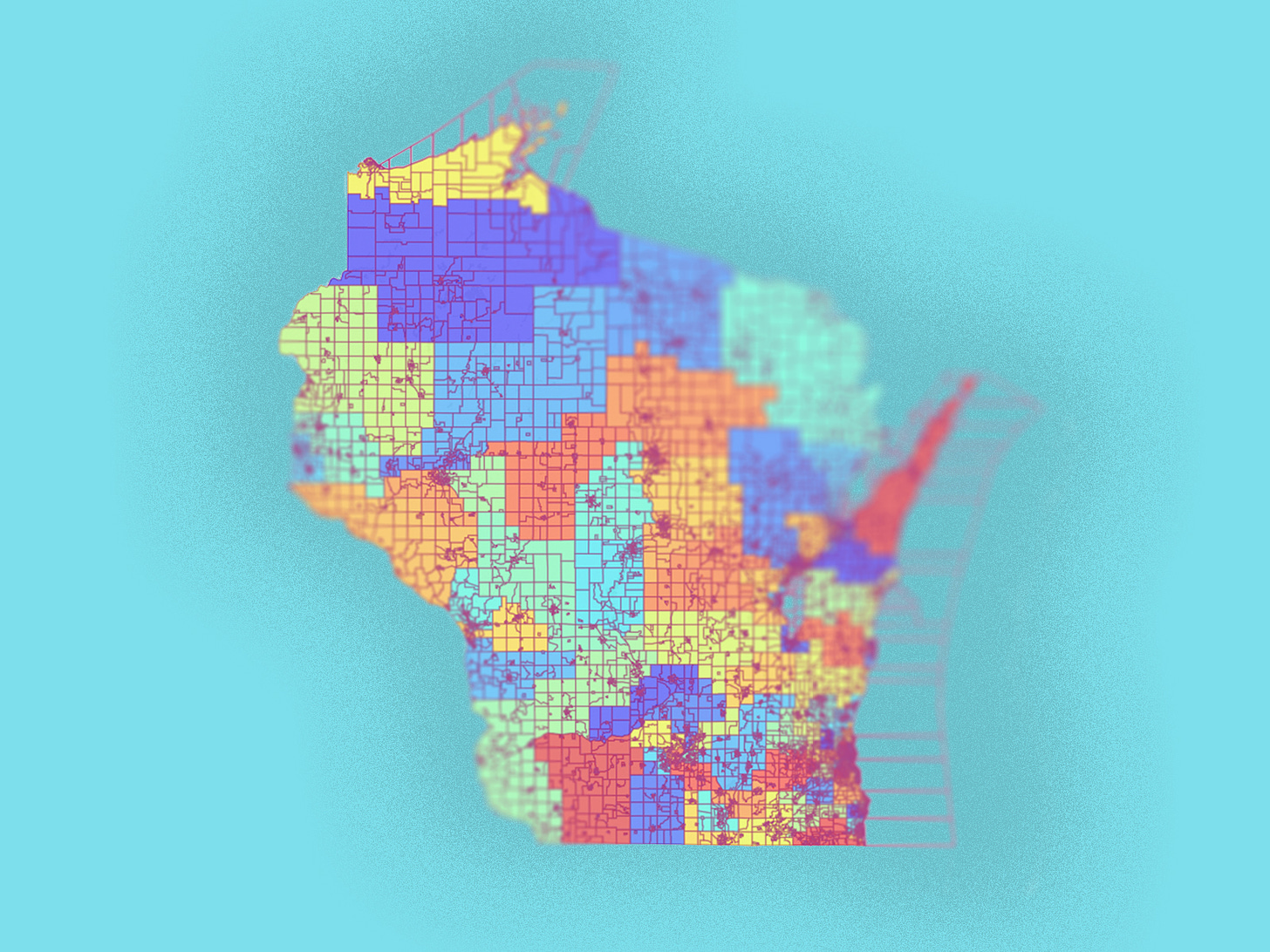

Now that Gov. Tony Evers has officially signed fairer state legislative maps into law, Wisconsin is on the verge of elections under un-gerrymandered maps for the first time in over a decade. I don’t want to rain on anybody’s parade—the new maps are a huge step in the right direction. There’s a lot of easy fixes with widespread popular support that would move the state in the right direction: abortion access, BadgerCare expansion, marijuana legalization, restructuring shared revenue, removing laws that limit local control, implementing paid family leave, subsidizing child care, and investing in our schools, especially our university system.

But Democrats, with that zero-sum, “only-invest-where-we-can-win” strategy, have divested from heavily gerrymandered, often rural areas. Democratic campaigns in those areas are going to be functioning as startups that have to convince their audience that even though they’ve been ignored for years, “we really care about you now.”

The national Democratic Party didn’t even wait until February to shoot themselves in the foot in rural Wisconsin. January 29, House Democrats announced a list of 17 districts in their “red-to-blue” program, essentially giving potentially flippable districts a head-start with fundraising and campaigning. They supposedly focused on districts that were narrowly lost in 2022.

You know which Wisconsin district fits that description, but is not on that list? Wisconsin’s Third Congressional District, AKA, the district held by Democrat Ron Kind for 26 years and is now held by Derrick Van Orden, the guy who likes to bully librarians, curse at teen Senate pages, and skip out on House Speaker votes so he can play soldier/scholar in Israel. In 2022, Democratic candidate Brad Pfaff lost to Van Orden—but only narrowly, even though national Democratic groups decided to pull TV ads for Pfaff at the last minute. Wisconsin’s Congressional districts remain gerrymandered, though there’s a lawsuit that’s been filed to address them as well.

As someone who has followed and cared about rural politics for a long time, it’s particularly frustrating because if Democrats got out of their neoliberal 1980’s/1990’s worldviews and actually listened to progressives, they could make a really strong case for rural America.

Lots of people have pointed out we’re in a wave of 1950’s and 1960’s nostalgia. Which rightfully raises the hackles of Black people and women because those good ol’ days precede us having access to our basic human rights. But for rural America, that time period was the heyday of the family farm and rural life, a boom for rural America brought about by big government, regulation, and Democrats via The New Deal. The Great Depression prompted real, substantial changes, instead of the half-hearted measures along the edges of existing systems that we see proposed today.

For one, The New Deal implemented a system to manage the supply side of agriculture by buying excess products and setting a floor for commodity prices. Then, if there was a bad year, those reserved products would be released into the market to make sure food prices remained stable. We still practiced this to some extent into the ‘90s (government cheese, baby!) but a smarter component of the New Deal prevented overproduction in the first place and another Dust Bowl: pay farmers not to plant some of their acreage. I know some people look at fields of corn and soybeans and see nature, but ecologically those fields are dead and the soil so depleted that one drought could blow most of it away. Why do you think we have so many issues with nitrogen and phosphorus overuse and runoff? Farmers have to add these fertilizers to the ground because there’s so few nutrients in the soil. Sprinkling some cover crops and leaving some fields alone for a season or two can mitigate those issues, especially nowadays when we have learned so much more about what to plan to restore soil health.

That era was then destroyed by the Republican policies of deregulation and prioritizing industrial agriculture, initiated by President Richard Nixon’s USDA secretary, Earl “Rusty” Butz, champion of big agribusiness and fast food. Since then, farms have gotten bigger and farm-adjacent industries—seed companies, equipment sale and repair, slaughterhouses, and creameries—have all become so consolidated that economies of scale are no longer about profit, but survival. I spoke with one dairy farmer who said the nearest creamery was three hours away. That means he needs to have enough cows to fill a truck that is big enough to still be profitable after driving six hours. That also means that whatever price that creamery sets is what that farmer is going to get, whether or not it keeps them in the black. Because where else are they going to go?

Some defenders say, “What’s the big deal? We’re still producing a lot of food, just on larger farms?” The big deal is that rural America is dying. Fewer families on farms means fewer kids in local schools, and fewer families going into town to bank, eat, and shop. And when I say “dying,” I am not being hyperbolic. Rural America is dying of age: its population is getting older because the dearth of career opportunities—farming and otherwise—drive young people away, even if they want to live in a rural community.

Rural America is dying from substance abuse; Opioids have garnered more attention due to the lethality of fentanyl, but before that there was meth and alcohol. My first newspaper job was in rural Nebraska. The crime and courts reporter told me that if we reported every time someone got caught with meth, that would be the entire paper. And I avoided country roads at night because of how many deliriously drunk drivers I encountered.

Rural America is also dying by its own hand; farmers are three and a half times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. While I appreciate Sen. Tammy Baldwin adding an investment in rural suicide prevention and mental health resources to the Farm Bill, the real root of the problem is the ag economy. If we want to save rural Americans, we need to implement policies that give people hope that their hard work will be rewarded.

Those same Republican policies are the root of a lot of organizing in rural communities against concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, extremely large and concentrated animal production sites. Unsurprisingly, this unnatural concentration of livestock (we’re talking hundreds, even thousands of animals in a small area) causes all kinds of problems that affect their neighbors' quality of life. The response from Wisconsin Republicans is to limit local control, supposedly to protect farmers.

Wisconsin’s new maps are an opportunity to reshape the state’s landscape, but it’s not enough to try to get rural voters to swap from R to D. There’s a great deal of distrust of politicians full-stop, and of Democrats in particular, and for good reason. Democrats need to deliver, not on the edges of problems, but by implementing massive, structural changes that would, frankly, make life better for all of us. The new maps are an opportunity, but only if we seize it.

I mean, even way back when [old man shouting at clouds voice] when the Democrats were sort of in power, they didn't do that much to help rural people. I mean, the Chuck Chvala years? Blargh.

Rural folks often see Democrats as career politicians who only care about getting re-elected. And a lot of times, it doesn't seem like they're wrong.

It feels like it's all about who can talk a better cultural buzzword game to the people they see as rubes, while shoveling money at landlords and big business. But I'd love to see state policy turn around and start rebalancing the scales. Here's hoping we can hold anyone to it.